Not long ago I had the pleasure of hearing a choral performance of Even When He Is Silent, an anonymous poem set to music by the Norwegian composer Kim André Arnesen. While I can’t provide a video of the performance I heard, fortunately you can hear a lovely rendition conducted by Anton Armstrong by clicking the link to YouTube, located here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hYwYMngq4II

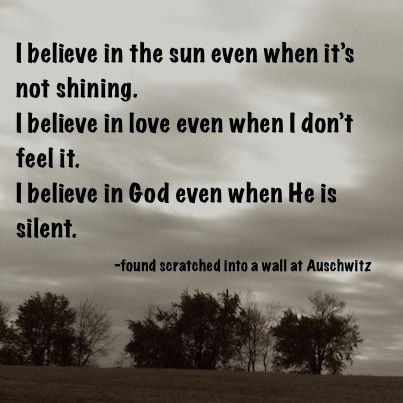

The words express deep religious conviction, and the musical setting by Arnesen does them justice. The lyric is short and goes as follows:

I believe in the sun, even when it is not shining.

I believe in the sun, even when it is not shining.

I believe in love, even though I don’t feel it.

I believe in God, even when he is silent.

The liner notes identified the poem as originating on a wall at Auschwitz.

While I was deeply moved by the sentiment, the music and the superb performance by a talented group of singers, my historian’s sense was pricked. My period is the ancient world, so it is no surprise that I might not know a composition emanating from the era of the Holocaust, but there is something about this language that strikes me as a little too pat for what I would imagine a concentration inmate inscribing at Hell’s portal. I thought to myself, I wonder what the original language of this poem might say? I expected to find that original language to be Yiddish or German, perhaps even French. I was quite certain it wouldn’t be English.

Of course I turned to Google–where else does one go at first these days for such things? I expected to find some recent quotations and a link to some article or book where the original text would be cited. Much to my astonishment, there was no such link! I spent hours looking at everything Google retrieved for me, but all I could find were articles that quoted the poem in English. I did find one version of it in French, but that was clearly a translation of the English, not a claim to have the original language.

One issue was quickly resolved. Whatever the provenance of this quote may be, it has nothing to do with Auschwitz. There is a reason why many people associate it with Auschwitz, though. In January 2015 a public ceremony was held at Auschwitz and Prince Charles of Wales read the poem there. An example of how the poem is described that day from the (England) Telegraph [“Survivors remember Auschwitz: ‘Every time I come here I feel fearful'”, 1/27/15]:

The Prince finished his short speech by reading out a three-line anonymous poem scratched on to a wall by a victim of the Holocaust.

Notice that the journalists make no claim the poem was discovered at Auschwitz itself. It’s just “a wall”. But they do go so far as to state it was written by a victim of the Holocaust. There is no indication of why they believe that to be the case.

Another surprising result of my search was that Google could not find a single example of this quote earlier than 2005. If the quote was discovered in some connection to the Holocaust, written by someone in a camp which was discovered at the end of the war, how likely is it that the first time it is cited is 40 years later?

If you run your own search you should find what I found. One set of articles that attribute the quote to a discovery in the German city of Cologne. Another set that seems to contradict the first. But none of these articles or links is earlier than 2005 (that I have found so far), none quote the poem in it’s original language, and none provide any evidence that the poem had some connection to the Holocaust or a Jewish author.

My preliminary conclusion is that this story is a false attribution. The poem was written in English and circulated anonymously. Someone thought that it sounded like what might be the words of a person in a bleak place such as a bombed out city or concentration camp. Someone else heard this, loved the poem, and posted it as if it were exactly that.

This sort of phenomenon is not at all unusual. There is a beautiful song composed in Yiddish and made famous by (of all people) Joan Baez called Dona Dona. (On Baez’s recording, the song is named “Donna Donna”.) The first line of the lyric is “Calves are easily bound and slaughtered Never knowing the reason why.” Early in the history of this song, someone believed it to be the work of a Concentration Camp inmate or survivor, and there are not a few references to it that way. In fact, it was written by two American Jewish artists, Shalom Secunda and Aaron Zeitlin, and it had nothing to do with the Holocaust. It was written for a play that began its run in the New York Yiddish theater in 1940.

Another similar error occurred in 1967. The Israeli artist Naomi Shemer composed a beautiful song about Jerusalem, Jerusalem of Gold. After the Six Day War, it became an anthem for those who were delirious over the reunification of the city. Large numbers of people are convinced that Shemer composed the song out of nationalistic pride at this event. But the truth is that she wrote it several months before the start of the war, so it is not possible that she composed it as some sort of victory chant.

I am mindful of one of the important principles of my profession: “The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” In other words, if I simply rely on my statement of the absence of a citation, that evidence can be disproved simply by discovering an earlier quote. The closer in time to the end of WW2, the more likely it becomes that the quote has authenticity. And so rather than state my conclusions as some sort of absolute, I would rather post it as a query. Has anyone found this quote cited, described, perhaps even photographed in situ at a time closer to when it is alleged to have been composed?

There are four stanzas to Jerusalem of Gold. Three were written a few months before the Six Day War. After the war, Noami Shemer wrote the jubilant fourth stanza “We have returned…”. That’s what made it the “theme song” of the war.

My search experience is similar. I can push a citation back to 1998 at which time it appears in “The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Jewish History and Culture,” in which the lines are attributed to an ‘anonymous author’ in a ‘cellar in Cologne’. I consider the lack of earlier references or citations significant.

Whoa. Someone with better skills than we have has tracked it back to July 1945, and what a story is there: https://humanistseminarian.com/2017/03/19/i-believe-in-the-sun-part-i-look-away/

Thanks for this reference. I think I saw it (or parts of it) before it reached the conclusion. Note that while it does take the story back to edge of World War 2, we are still left wondering whether there is any truth to it. A fascinating journey is sometimes better than a quick resolution!

There are references to this poem back in 1947. I read an extensive series of blog posts about it and its origin. A POW in England quoted the poem in a BBC interview. So, it is German. It is from Cologne and it is from WWII.

This is so interesting..I remember performing a choral arrangement of this poem as a child in 2004, so not much further back than the earliest citation you found; we were told the lyrics were written by a victim of the Holocaust. I’m almost disappointed to hear it may very well not have a legitimate origin story!

Carey Landry was a popular Catholic musician producing music in the 1970’s-1980’s. I learned this song in Catholic school in the mid-80’s:

Fascinating. I have found the words so helpful in dark times – and perhaps especially so in these days of pandemic.

Thank you all for your diligent research. Truth is always good to know… even if our fond imagination might be more comfortable…

I first heard this poem when I spent a few weeks on a teen tour through Eastern Europe and Israel in 1990. At the time I was told it was found scratched on the wall of a prison cell.

A primary source has been found with a Swiss journalist claiming to have read it from a cellar wall in Cologne: https://humanistseminarian.com/2021/04/04/i-believe-in-the-sun-part-v-the-source/

My understanding is that the original poem was found written on the wall of a cave in France . Written by a teenage girl that fled to the cave to escape persecution as a Christian. She died of starvation and the poem was written on the wall. It was discovered later possibly happened in the sixteenth century.

Dear Linford, welcome to my blog! I don’t post very frequently here, so if you follow the blog, you will not be bombarded with large numbers of posts or spam.

Thank you for your comments. I am unaware of any evidence that the poem dates in any way prior to World War II. There is an ongoing lively discussion as to whether it was written by a Jew or Christian (most likely Roman Catholic). If you would like to see what is in my opinion the best appreciation of the work, a Web page called the The Humanist Seminarian has been posting regularly and reviewing all the evidence since 2017. The series has now reached 5 articles, and you can find the first one here:

Humanist Seminarian on I Believe in the Sun

My apologies, Cameron–I didn’t see this when you originally posted it.

— Jack Love

I will add a tidbit that doesn’t resolve the source but puts another dot on the timeline.

I received a poster from my father when I went to college in the fall of 1970. I loved it. It meant a lot to me that he picked out a poster of this poem, printed simply against a background of a setting sun, in oranges, reds and blacks. My father just died at age 103. Looking back on our relationship, I think of this poster.

I’m pretty sure the middle line on the poster was “I believe in love even when I’m alone”. The first and third lines were the same as your quote.

I assumed at the time that it was an inspirational poem created for the 1970’s poster market. The poster is long gone but the words have come back to me over the years, and the warmth of remembering how touched I was by my father’s gift.

Back in the early 80’s, a dear friend painted a floral picture with this quote as a gift to me, and it was the not the first time, that I had heard this quote. I am 66 now. My husband read years ago that it was found inscribed on an insane asylum in the 1800’s……. who knows…..

Thanks for the comment. FYI, I am trying to save myself a little time by combining my two WordPress Blogs. Eventually, all these posts will be moved over to blog.loveleefamily.net.